What is your attitude towards climate change?

What is our, your, attitude towards climate change? Are you more conservative, cornucopian or rebellious? Each attitude corresponds to an aspect of the energy transition. We each tend to favor part of the efforts to be made to eventually converge towards carbon neutrality (no net carbon emissions in 2050).

In absolute terms, these three dimensions must be inscribed at the same time, in the same dynamic. This is why this period of rupture is complex because everyone uses their own means to assert their point of view.

The attitude can be rather passive with the conservative, reflect the power of the power in place with the Cornucopians or even provoke violent reactions, at the limit of democracy sometimes with the rebels. The justification then is to consider that this is the only possible way to take their point of view into account.

What this breakdown also shows is that everyone does not have the same time scale, the same scale of urgency in the face of climate change. We must not hesitate to be out of step with the scale of the issue.

Can we be conservative?

We are conservative when we think that the man will eventually get out of it. He always has and it's only a matter of time. Consequently, it is not a question of rupture but rather of arbitration today and in time.

The key element is energy efficiency, which shows that for decades the energy needs per unit of production have frankly decreased. It is then enough to continue on this momentum and to improve here or there so that finally a solution can be found to the question of the climate. We change cars to go electric, we install solar panels or we sort waste. All these factors are important to change the framework and allow a good adaptation to the new world that awaits us.

But that is not enough.

The preferred tool of the conservatives is the carbon tax, or Pigou tax for economists. By playing on the price of carbon, it will, over time, alter the choices but not generate the disruptions necessary to stay on the right trajectory. This is the discussion between growth and emission. France and many other developed countries continue to grow (increase in per capita GDP) while reducing their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Developed countries are virtuous with regard to this statistic. The carbon tax would make it possible to accentuate the arbitration in favor of an additional reduction in emissions in order to converge towards the objectives necessary for carbon neutrality.

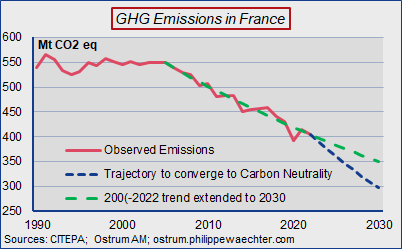

In France, the break took place in 2005. Since then, emissions have been trending down at a rate of just under 2% per year.

This vision, which has a reassuring dimension, is however not sufficient.

By following the trends, France, to take an example, is not converging towards the objectives it has set for 2030. To align with the European objectives, it is necessary to reduce GHG emissions by 55% compared to 1990. We see on the graph that the trajectory to follow (blue) is much lower than the trend observed since 2005. We must go faster.

The policies implemented are not sufficient to think of converging towards carbon neutrality in 2050. They are in the process of adjustment while a break seems necessary.

Being conservative is not enough to stay in a sustainable universe.

Can one be Cornucopian?

We are cornucopian when we think that human genius will make it possible to face the limits encountered (see here the fascinating article, in French, by Aurélien Boutaud and Natacha Gondran).

Cornucopia, in Latin, is the cornucopia, the one that does not dry up. It is human genius, the ultimate and inexhaustible resource, which will make it possible to deal with all situations in which resources are limited.

It is technology, the result of this human genius, that will make it possible to overcome physical limits. The problem then does not come from these limits but from the ability to exploit them. It is the technology that will allow it by improving the capital.

To produce, capital and labor are needed. Technical progress will be integrated into capital. Capital can replace labor or even natural capital. Therefore, since capital can grow infinitely, growth can be long term.

The response to climate change is then at two levels:

If the density of carbon in the atmosphere must be reduced, then investments in carbon capture technologies must be rapidly and strongly developed. This can be done either by capturing it in the atmosphere (DAC technology for Direct Air Capture), or by capturing the carbon leaving the factories (CCS technology for Carbon Capture and Storage). I mentioned this question in a post, in French, in July (“Innovations and Climate Change”).

We must promote new energies that will replace the fossil fuels that are the source of carbon emissions.

These two points are important.

A - Firstly because governments (US, France, UK in particular) invest considerable resources in developing carbon recovery technologies. Which raises four questions:

Why not pay more attention to natural carbon sinks such as oceans and forests? They are much less expensive.

Why systematically go through oil exploration companies to implement them? There are billions at stake. We saw this recently with the Cypress project in Louisiana entrusted to the oil company Occidental Petroleum. The operation will benefit from a public subsidy of $1.2 billion and a windfall of $120 per ton sequestered. The icing on the cake, the reinjected carbon will make it possible to bring out the oil that is difficult to exploit.

The technology is not very efficient. In the Cypress project, the volume captured will be 1 million tonnes per year. This is the size of emissions from two wheels in France over a year. It is expensive per ton sequestered, much more expensive than a ton sequestered in the forest. The big factory in Iceland to recover carbon via DAC technology can capture the equivalent of the emissions of 800 cars over a year!!!!!

This without taking into account the associated technological uncertainties. Is carbon injection reliable over time, in other words, will there be leaks like with methane? What are the consequences for the stability of the places where the carbon will be injected? During fracking experiments on gas and oil, this weak point has often been highlighted. Should we continue?

B - On the second point, we observe in the past that the energies were more complementary than substituted. In other words, the new energies, if one follows the past evolutions, are added to the existing energies. We cannot dismiss this argument because in 2022, the consumption of fossil fuels registered even higher while renewable energies progressed rapidly, prompting the International Energy Agency to have great optimism.

A final remark on this point: since the industrial revolution, this vision of the world has won. The world has developed, driven by technological progress.

However, aren't the evils from which we currently suffer the measure of the excesses generated by this dynamic? Are we able to replace nature in an infinite way? Isn't the issue of climate change a questioning of this movement observed since the industrial revolution?

Can we be revolted?

The last way to perceive climate change is under the rebellious view.

The argument is very direct: since GHG emissions reflect the large-scale consumption of fossil fuels. To remain in a sustainable world, we must quickly reduce emissions and therefore the consumption of these fossil fuels. This is a necessary condition to converge towards carbon neutrality.

The graph shows that the consumption of primary energies (oil, gas, coal, hydro, renewable and nuclear) continues to grow and that fossil fuels still have a significant weight.

In 2022, fossil fuels (oil, gas and coal) accounted for 81.8% of primary consumption. No break is observed in this consumption with the perception that the use of renewable energies adds up rather than replaces fossil fuels. This is not the right scenario for the new available energies (renewable) to replace fossil fuels.

This element is major because moving towards carbon neutrality in 2050 and remaining more or less within the framework of the Paris agreement presupposes that this consumption of fossil fuels is at least halved by this horizon (BP has calculated that it should only be a little over 20% of all primary energy consumption).

If there is no reduction in fossil fuels and substitution with renewable energies, no one will fall within the framework of the Paris agreement.

This absence of rupture is observed everywhere. The following graph shows the weight of fossil fuels in primary energy consumption. (In Japan, the 2011 rupture corresponds to the shutdown of nuclear power after the Fukushima tsunami and France benefited from its large nuclear program implemented when Pierre Messmer was Prime Minister at the time of the first oil shock).

When the issue of fossil fuel consumption is put forward as a necessary solution to global warming, there are two kinds of attitudes.

That of scientists who have long pleaded, coldly, for the reduction of this consumption. This would make it possible to quickly reduce GHG emissions and have every chance of coming within the framework of the Paris agreement.

However, they are not the ones we hear the most except at the time of COPs and possibly climatic events.

The other attitude is more rebellious, more assertive and often more brutal. We know the always piquant interventions of Greta Thunberg, but what we often remember are graffiti on paintings in museums, sit-ins on the ring road of a metropolis or more radical and frankly violent positions.

Among the rebels, there is the need to speak out on an urgent point when the rest of society does not seem to be alert. The conservatives, the majority of the population, are worried but without excess, the governments are rather Cornucopian and optimistic. Therefore, it is necessary to leave the usual framework of societies to be heard.

Albert Hirschman in “Exit, Voice and Loyalty” indicated that when the process of natural adjustment (defection) within societies, it was necessary to be more radical via stronger positions (voice). The rebels speak out in societies that do not move fast enough according to them. The process is large enough, in number of people, to be meaningful.

These rebels do not form a homogeneous group. There are those who are frankly concerned about climate change and there are those for whom the climate issue is only a means to radically change society. This is why the movements are not very clearly identifiable, creating confusion between choices frankly associated with climate change and those primarily reflecting political positions.

Suddenly reducing GHG emissions means quickly reducing the consumption of fossil fuels with a strong risk of a marked and lasting decline in GDP and employment. This is a bit like what we saw in 2020. But the year of the pandemic was special because it was assumed that the health risk would only be temporary. Consequently, States could intervene to avoid a rupture. It worked pretty well.

On the other hand, if the adjustment were to last a long time, the risk to activity and employment could be high with a significant associated social risk. This would reflect a lower level of activity but also real changes in our consumption habits (auto for example but also how to heat our homes).

The impact would be strong on the way we build the world (cement, plastic, steel or even the ammonia needed for fertilizers). We would quickly change register, which is also why we can regret the limited efforts observed since the fall of 2006 and the report by Nichola Stern which had put the climate issue at the forefront.

This point is difficult to accept for the majority, but it is the support of many views on the establishment of a new society or a dynamic of degrowth (I will come back to this point very quickly).

Conservatives, cornucopians and rebels are the three components of society in the face of climate change. The points of view and the value of time do not seem compatible, the urgency is not the same. For the conservatives, changing current behavior over time will be enough, for the Cornucopians, time goes hand in hand with the emergence of human genius, while for the rebels and the scientists, the break must take place very quickly.

And you, where are you?

________________________________________

Philippe Waechter is Chief Economist at Ostrum AM in Paris