What future for inflation and interest rates ?

The world is changing and with it the modes of adjustment of the global economy. Inflation, which has been very low for thirty years, will register at a higher level over time.

The economy is changing, it is no longer that of globalization at all costs, it is becoming that of relocation and energy transition. A higher rate of inflation will help this transformation.

The higher inflation rate will restore the full role of the traditional modes of action of central banks and less appeal for asset purchases by the monetary authorities.

The other point is that the investment needed for the energy transition will result in a higher demand for capital. This will result in higher long-term interest rates which will return to levels compatible with their role in allocating resources over time.

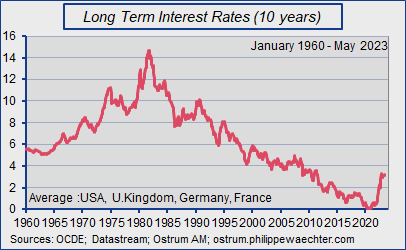

The world is turned upside down. The pandemic, inflation, the war in Ukraine, the awareness of climate issues or even the tense relations between the United States and China suggest that the world of tomorrow will not be a replica or an extension of the past. It is irrelevant to think that the framework in which the world economy will operate for the next 5 or 10 years is a copy of what happened from the financial crisis to the health crisis. This point on the scale of the global economy must be extended to the financial markets and in particular to long-term interest rates, the profile of which has been downward since the beginning of the 1980s with the financial globalization that took hold during Ronald Reagan's presidency. This long period ended with the return of inflation and restrictive monetary policies

This long downward trend in long-term interest rates greatly benefited the banking and financial sector by revaluing all assets.

Five remarks:

The long phase of financial globalization is concomitant with a trend towards disinflation in all developed countries. In many studies, this common factor explains a large part of the fall in inflation and then its stability at a very low level.

As long as globalization is the major macroeconomic factor, the risk of a resumption of inflation was of low probability.

Each country also had an interest in not having an inflationary bias in order to remain competitive. Financial globalization has played a major disciplining role in economic policy behavior. France is well placed to know this.

The low level of energy prices even though the price of oil fluctuated before and after the financial crisis. Deflated by consumer prices, the price of a barrel of Brent is at the same price as after the second oil shock, before the long period of the oil counter-shock. We also see that the price of oil never settles on a permanent upward trend.

The battle between producers is generally the source of fluctuation in the price of black gold. This is why they should not be counted on if the objective is to drastically reduce the consumption of fossil fuels. The carbon tax will surely be more effective

Globalization has also had the effect of reducing the bargaining power of employees in industrialized countries. The threat of relocation of production tools with its negative counterpart in terms of jobs has been a weapon that has kept wage rates relatively low without preventing the development of jobs elsewhere and without reducing the phenomenon of deindustrialization either.

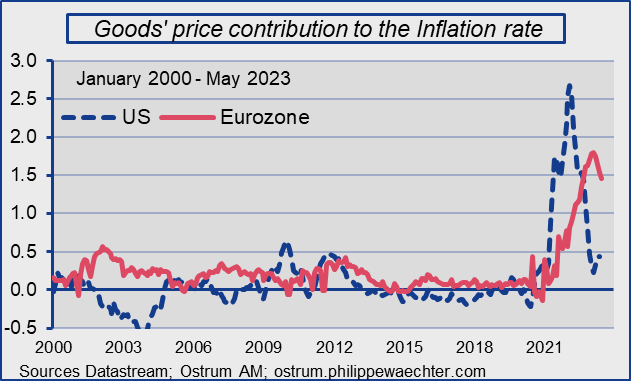

This is a point developed by Joe Biden since his presidential campaign around the concept of “middle class economic policy”.This globalization of the economy has been a major source of disinflation for Western countries. The relocation of production and its development in emerging countries have led to lower costs and very competitive import prices. From 2000 to 2020, the average contribution of the price of goods to the inflation rate was close to 0 in the Euro zone and zero in the US, we must see the effects of this relocation of production.

Central banks have been credible in managing inflation. For the 4 reasons mentioned above, inflationary pressures were limited and when inflation rose sharply, mainly due to the rise in the price of oil, it never really lasted because the relay on wages was not marked.

The role of central banks has therefore been to create the conditions so that nominal tensions do not exist apart from energy-related effects. This is why they generally responded more to activity signals than to price signals.

These factors have kept the inflation rate stable and low in developed countries. Now they are partly faded.

Globalization no longer has exactly the same form as in the recent past. China no longer has the same status. From a source of impetus for the global economy, it has become a subject of mistrust. Companies are banned in some countries including Europe and the US has drastically reduced the possibility of transferring technology. The common dynamic that radiated allowing a long phase of disinflation and an efficient allocation of resources is no longer the dominant factor. In any case, we can no longer assume that the contribution of the price of goods, the main driver of disinflation, is close to 0% as was the case from 2000 to 2020.

In addition, the situation is more complex because China remains a country where there is a lot of assembly of technological products on which developed countries are very dependent. China could bet that the relocation of activity within Western countries will not be as marked as expected in developed countries, at least not for all imported products.

This would allow it to fix the prices of these products at the level that the Middle Kingdom will determine, at the risk of causing a bullish bias on the contribution of the price of goods for developed countries. It is a dimension of the balance of power that is being established. The change in the pace of globalization will also have an impact on the labor market. This will no longer be as broad and in fact, employees will regain bargaining power in discussions on wages. The threat of investing elsewhere has thus found its limit.

We will also see what happens to the behavior of central bankers after the current episode of inflation. Could they keep the same type of inflation target if the trend inflation rate is a little higher. But what is price stability? We can expect a generalization of fuzzy targets as defined by the US Federal Reserve, which indicates an average inflation rate of 2% in the long term.

Inflation will not be the same

Besides these elements that have changed, the economy is also upset by other factors. Climate change and the energy transition is a new framework in which the global economy will have to fit quickly. The reduction of greenhouse gas emissions will only find its reality in the decline in the use of fossil fuels. This will require increasing the cost of using these energies. In the short term, we welcome the fall in the price of gas or oil for cyclical reasons, but this is not compatible with the energy transition. In a recent paper, Christian de Perthuis thus indicates that the reduction in emissions in France is not compatible with the Low Carbon Strategy. Since 1990, these emissions have fallen by a quarter following a trend of -1.8% per year. To be in phase with the achievement of the objective of -55% in 2030 (compared to 1990) it is necessary to move to a decline of -5% per year for the remaining years. How to do it without affecting the price?

The price must increase to discourage the use of fossil fuels. To put it another way, the real price of oil has changed little over the past forty years and the share of fossil fuels in primary energy consumption is relatively stable and still above 80% in 2021 (in the waiting for 2022 figures by BP).

To fix ideas, the scenario associated with carbon neutrality in 2050 suggests a consumption of fossil fuels close to 20% (BP Energy Outlook 2023). In view of current behavior, the projection for 2050 is 59%. This is much less than currently but almost three times higher than the neutrality scenario. The price will have a key role in the future evolution of the consumption of gas, oil and coal.

The other point is that the increase in renewable energy consumption will be multiplied by 4.5 in 2050 while remaining in the carbon neutral scenario. It must increase from 14% of primary energy consumption to 64% in 2050 to respect neutrality. At the same time, the share of electricity in final energy consumption is expected to increase from 21% in 2021 to 51% in 2050 (according to BP Energy Outlook 2023).

These data to indicate the complete reversal of the development model and a demand associated with renewables and the production of electricity which will upset the market for raw materials, the market for what is useful for these developments.

There too the price of certain commodities will increase rapidly. The level of prices will be strongly affected but also their volatility. The transition will not be a long road made of tranquility.

Moreover, this change in the prices of raw materials will not be without geopolitical consequences because the reserves of these materials not yet transformed are often located in countries which are not those which currently have the fossil fuels which have made them rich.

For the moment, the effort is insufficient to stall on the virtuous trajectory. All of these adjustments will be made by the will of everyone, by massive investments but also by prices. We cannot assume that these radical changes will be neutral on price dynamics, otherwise prices no longer play a role in macroeconomic adjustment. It's a bit excessive.

On this point, we can cite the words of Alan Blinder who, analyzing the inflation of the 1970s, indicated that the transformation necessary following the rise in the price of oil and the structural changes at work at the time required a rate slightly higher than that associated with price stability in order to facilitate adjustments to get on the right trajectory.

What dynamics for long-term interest rates?

As a trend, the inflation rate will be higher than that observed for twenty or thirty years. This corresponds to the upheaval of the world, to the change of balance. The framework for coordinated and cooperative globalization is partly complete. The balance of power between the great powers now guides international relations with a particularity that reflects the strong economic dependence between the major regions of the world. In the past, such a situation was not observed because economic or political rivalry was never enough. This is no longer the case. It is a new situation.

The global economy will no longer be able to be as well coordinated as in the past.

A higher trend inflation rate should cause higher long-term interest rates over time. We must bear in mind what happened in the 1960’s. The rise in inflation, due in particular to tensions on the productive apparatus, only resulted in higher interest rates with time limit. The phenomenon is symmetrical when inflation declines, the interest rate takes time to adjust to a new equilibrium. While I do not believe in an inflation rate that would settle at levels comparable to those of the 1970’s, it is likely that an inflation rate, for all the reasons mentioned above, would result in rates permanently higher interest rates.

This inflationary phenomenon is essential for understanding the profile of interest rates. We can add three other phenomena.

Central banks will recover the management of short-term interest rates. These will no longer be condemned to be close to 0% as has often been the case since the financial crisis.

The reason central banks bought assets on a large scale was because their own interest rates were hitting the low limit of 0%. By regaining room for maneuver on short-term interest rates, the monetary authorities are putting these unorthodox measures in the background. Barring a large-scale shock, the attitude of central banks will no longer make it possible to keep long-term interest rates low over time. This is normal due to higher inflation. This will also have disciplinary virtues on budgetary policies since the debts issued will no longer be purchased by the banks of issue.Potential growth will be at the heart of the issues raised over the next few years. Relocation and industrial policy, which are two sides of the same coin, aim to revitalize industrial activity and the productivity associated with it. If indeed this strategy is effective, then potential growth will be stronger, validating higher real interest rates.

In a remarkable remark highlighting excess savings, Ben Bernanke explained, in 2005, the low level of interest rates by this imbalance between excessive savings and insufficient investment. Regardless of inflation issues, the real interest rate reflects the balance between savings and investment.

In the coming years, the need for investment to meet the energy transition will be considerable. Jean Pisany Ferri and Selma Mahfouz spoke, in a recent report, of 70 billion per year across France to meet this objective. Massive investment will drive up long-term interest rates. The real equilibrium interest rate will certainly be higher than that observed in recent years.

The world is changing, and interest rates are regaining the power of intertemporal resource allocation.

_______________________________________

Philippe Waechter is chief economist at Ostrum AM in Paris