The Brics at 11 or the definition of a new global balance

The expansion of the Brics from 5 to 11 countries is not anecdotal, it is a radical change in the global balance.

Until now the Brics group (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) was only an intellectual construction of a brilliant economist from an American investment bank. These 5 countries could share common interests but the total weight of the group was only the sum of the weight of each of the countries. It was by no means a construction capable of competing with developed countries.

The Brics mainly drew their geopolitical weight from the rise of China over the past twenty years, from the long-deceived hope that India represents or even from the warmongering fear that Russia had before the invasion of Europe. Ukraine.

Recently, the Brics had initiated discussions on the dedollarization of international trade. This movement, widely relayed by the press, lacks credibility due to the still considerable influence of the greenback on all transactions, whether commercial or financial.

For a possible changeover to make sense, it would have been necessary to put a unanimously accepted currency opposite the greenback. For the moment this is not the case. In international finance, Gresham's anti-law applies, which says that good money drives out bad money. That it would have the right currency likely to drive out the bad, the dollar in this case?

The Chinese yuan is by no means large enough in central bank reserves to play this role (a Financial Times chart circulated last week taking the dollar and yuan data and putting the yuan's share on the scale on the right giving the impression that the Chinese currency was competing with the greenback).

Moreover, due to the time needed to fundamentally change the financial dynamics, this operation would have taken an inordinate amount of time. All the longer since we do not know the substitute currency (the passage from sterling to the dollar occupied the period between the two world wars). It cannot therefore be a rapid factor in changing the world.

The enlargement of the Brics group is a radical change. The balance of the world can be altered in a lasting way, forcing developed countries to implement international strategies of a new nature.

Measured as a percentage of global GDP and in purchasing power parity, the new group represents 36% of global GDP in 2023 compared to 32% when only 5 countries participated. The most important point is to note that without China, the weight of the Brics at 10 in the world GDP has been stable since 1992.

Two remarks:

In his speech in Johannesburg at the Brics summit last week, Chinese President Xi considers that the Brics are the future but above all that the grouping is a relay of Chinese policy. Global governance must be redefined by Beijing, thus accentuating the balance of power with the West. The enlargement of the Brics therefore has a major political basis.

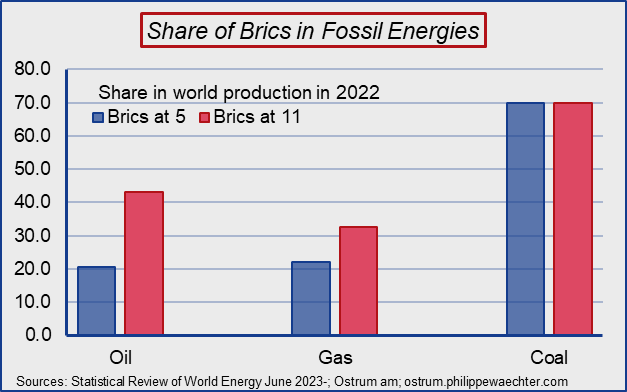

The second remark is that if the economic weight of the new group changes little compared to the old one, the structure of its resources is disrupted. The weight of fossil fuels held by the new version of the BRICS is becoming very important and given the role of these in the global macroeconomic dynamic, it is a considerable means of pressure for Xi's China.

Three points on which the current balance is upset

The first concerns the balance of resources. The new group will combine two of the three largest oil producers (Saudi Arabia and Russia), a major producer which is Iran. You could say similar things about gas

The period is that of the energy transition, when the consumption of fossil fuels will have to decrease. This grouping of interests is a game-changer. The objectives of the new group will not necessarily be compatible with those of the developed countries at the risk of marginalizing American production while bringing Iran back into the concert of nations.

In addition, by joining the BRICS group, Saudi Arabia, which was the friend of the US in the Middle East, is accentuating a policy of mistrust vis-à-vis Washington. On the energy issue, this will be important because the Brics have a production that now represents more than twice that of the United States.

The second point is that of the fight against climate change.

In 2009 at the Copenhagen summit (COP15), the sticking point was the very unbalanced contributions to carbon in the atmosphere of developed countries compared to emerging countries. The former emit less but the stock of carbon in the atmosphere is their responsibility. While for the latter, the accumulated stocks are reduced but the current emissions are very high. There is a marked catch-up effect of the south compared to the north.

Consequently, the countries of the South consider that they cannot be subject to the same constraints as the countries of the North.

The story is not the same between the types of countries and emerging countries wish to be able to develop without excessive constraints resulting from the energy transition. This is where COP15 stumbled.

This question will resurface because the balance of power will no longer be the same. One can imagine that the new group will structure itself more, thus creating negotiation and pressure bodies. The context changes.

The COP28 discussions in Dubai risk being upset by this new balance in the making

In a related way, this change of balance in the negotiation on climate change goes in the direction of proponents of degrowth who consider that the question of emissions must oblige the developed countries to reduce inequalities by being those who will make the effort the most. more important to reduce emissions. For developed countries this can be a source of social disruption, especially in Europe.

The third point of change is technological. For nearly ten years, tensions between the United States and China have increased, mainly relating to technological issues.

China at the beginning of its economic catch-up benefited from significant technology transfers giving it the means to eventually have an advantage over the Americans on certain innovations such as 5G or artificial intelligence.

Trump's halt to specific companies was followed by an American halt when Biden arriving at the White House blocked semiconductor contracts. However, this has not stopped China from continuing to invest. Huawei remains a formidable company despite the halt in US transfers.

I mention this point at a time when India has just sent a rocket to the Moon on a side not explored until then. The new group, if it is structured, will have major technological power

Again, if the new group is structured, it could have first-rate technology, being then able to define a technological standard different from that of developed countries.

These three points suggest a geopolitical balance of another nature with a political dimension on several aspects.

The first is in a way the normalization of Russia. It is now integrated into a group that brings together half of the world's population and more than a third of global GDP.

The second is also the rehabilitation of Iran condemned by the United States on the nuclear issue and subject to very restrictive sanctions. It is a strong political choice of China.

The third point is that the structuring of the new group with institutions, beyond the New Development Bank whose headquarters is in Beijing, will profoundly modify the international balance of power. The globalized and cooperative world is over.

For Western countries, the situation is changing rapidly.

First on the energy level. The dependence on the Brics is accentuated in particular on fossil fuels but also on a number of raw materials. The question of the energy transition arises in a different way. We know that the transition must go through less consumption of fossil fuels, but this can go through greater price volatility, which could be destabilizing.

The other political point is that the tensions observed in recent years relate to relations between China and the United States.

Reading Xi's speech, China finds new allies including Iran and bolstering Russia's interest. There is no doubt that the United States will have to find a major ally with Europe in this new confrontation, this new balance of power.

But is this in Europe's interest?

_______________________________________

Philippe Waechter is chief economist at Ostrum AM in Paris