With US yields rising, the rest of the world follows in their wake.

This surge is driven by two factors:

1 – the swift upturn in oil prices, which translate expectations of stronger demand and Joe Biden’s legislation on the energy sector,

2 – the stimulus package put forward by the new US President.

The euro area could benefit from this situation if the ECB maintains a very active stance over the months ahead to subdue interest rates, thereby widening the yield spread with the US and bidding up the value of the dollar. The recovery in Europe could ultimately be driven by the US revival once again.

********

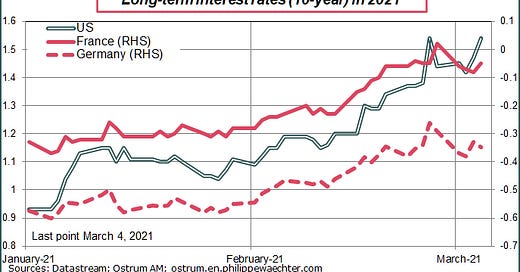

The jump in long-term yields marks the main change on the financial markets since the start of the year, with the US Treasury 10-year surging from under 1% at the start of 2021 to well above 1.4%. This uptick in US yields has also triggered a rise in European rates too, with the French 10-year even moving back into positive territory.

This yield swell comes as central banks have reiterated their determination to make further massive purchases on the public debt market. The monetary authorities’ purchase programs were a decisive factor behind plunging yields in 2020, and these institutions still remain very much in the picture, although they are not standing in the way of yields rising for now.

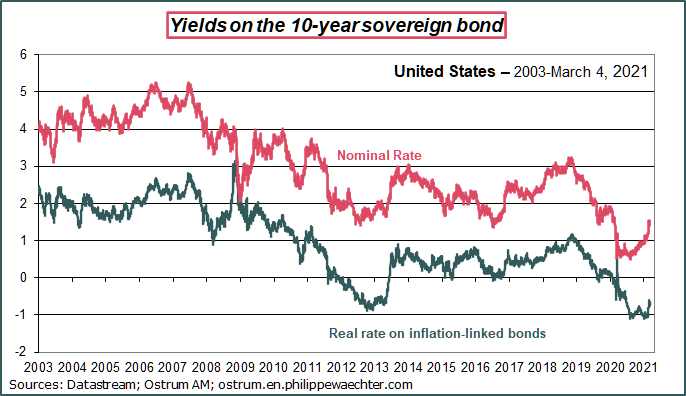

If we break down the US 10-year yield into its real component, which is measured via inflation-linked bonds, and the inflation component which is the differential between the nominal rate and the real rate, we can observe very different trends of late.

The inflation component surged very swiftly over the past few weeks, while the real portion is flat, apart from the last four points on the chart. The jump in real rates translates increased expectations of a pick-up in growth for the future, in line with the vote to approve the Biden administration’s stimulus package.

The uptick in inflation breakeven can be explained in two ways: on the one hand, the rise in oil prices, which fuels inflation expectations, and on the other hand, the effects of the Biden plan revaluing real rates.

A crucial role for oil prices

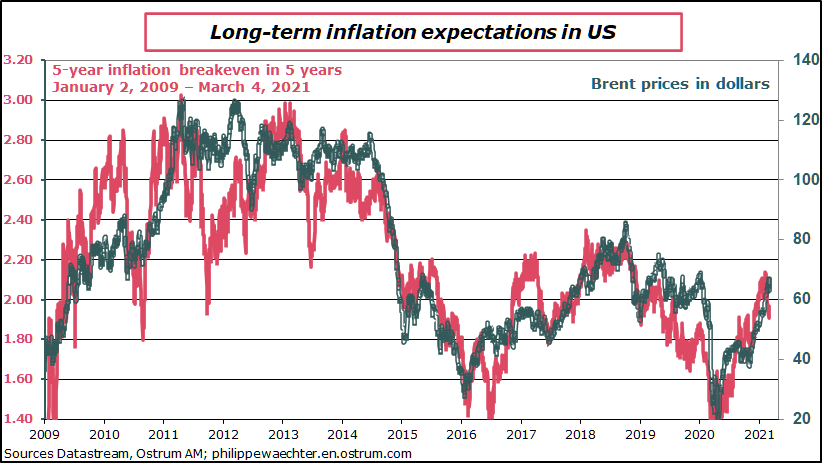

The chart shows a similar trend between the long-term inflation breakeven and oil prices. Oil price trends are reflected in the changes in expectations, both on the upside and the downside. This correlation is a gauge of the central banks’ – and the Fed’s – credibility, particularly if we look at this chart, for two reasons:

1- Central banks do not react to changes in energy prices;

2- And this is because shocks from oil prices have little knock-on effect on internal prices, as measured by either wages or core inflation.

Oil price fluctuations have no long-term impact on inflation, so therefore inflation volatility can be attributed to oil price volatility.

The recent upturn in oil prices would thus account for a large portion of the rise in interest rates.

The rise in oil prices has been driven by two factors that mark break points in price trends on the chart.

Firstly, the announcement of the Pfizer vaccine. This first vaccine and the ensuing inoculations announced will help get the economy back to normal and drive higher oil demand.

Secondly, Joe Biden’s decision to take a more ambitious tack on the fight against climate change than his predecessor. Recommitment to the Paris agreement on January 20, along with the January 27 executive order suspending oil and goal drilling on federal land, change the oil market’s structural dynamics, as the country aims for net zero carbon by 2050.

Joe Biden’s stimulus program

The other source of uncertainty is the Biden administration’s proposed rescue package, a $1.9trn program that has triggered heated debate among economists.

The White House’s aim behind this plan is to put the middle classes back at the heart of the US economy: this group has been affected by globalization over the past several decades and as such has seen its position deteriorate, while it was also hard hit by the effects of the pandemic. This program should be used to help the entire population, so it is preferable for it to be too broad rather than too narrow. Everyone will remember the 2009 rescue package, which was seen as too limited and failing to set the economy back on its pre-crisis trajectory.

However, this stimulus program could swiftly fuel tensions on the productive system and risk propelling an upturn in inflation, forcing the Fed to react to escalating prices: this idea has been put forward by Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard. Overheating of the economy can be measured by the difference between GDP at end-2020 and average GDP in 2019. The difference comes to -1.6% if we look at real GDP, while the differential is slightly positive (0.25%) on nominal GDP. The mammoth size of the Biden plan could drive demand, which in turn could lead to tension and fuel inflationary risk.

Two points on this debate are worth raising.

Firstly, unemployment has plunged from 10% to 3.5% since the 2009 financial crisis, while failing to trigger inflationary pressure. The chart opposite tracks figures from the cycle trough in June 2009 through to February 2020 just before the pandemic broke out.

The US economy’s ability to generate inflation looks weak in the short term. However, the 3.5% jobless rate is a far cry from the equilibrium unemployment rate, which is often agreed to be close to 5%.

The second point concerns the output gap.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has set out potential US GDP trends and it soon emerged that the economy would very quickly converge back towards this track, with the Biden package poised to further hasten this trend.

Estimates of potential GDP look more volatile than GDP itself, as suggested in the chart, and we note that after the 2009 crisis, projections were very high compared to performances actually observed.

The output gap – the gap between potential GDP and GDP effectively observed – is areassuring concept, but it may not be as relevant as we would like to think, particularly as the pandemic-related crisis has forced a rethink of the structure of our economies, with a number of sectors no longer able to operate in the same way as before.

The Fed doesn’t seem to be in a hurry, particularly as the bank views the labor market as uneven: qualified workers recovered from the shock to the labor market quite a while ago, yet the crisis continues to create shockwaves for less skilled workers. This fits with the point made by Jay Powell that jobless numbers are closer to 10% than the official figure of 6.3%. The Fed is making it clear that it stands ready to pursue major accommodation to get the US economy back on its feet again, even if this potentially means a little inflation. However, this is not a source of concern for the Fed, as inflation targets have taken something of a back seat in the institution’s reaction function. Inflation can now stand above 2% on a long-lasting basis, without the Fed having to toughen its monetary strategy, and the bank will not intervene dramatically in the event that inflation edges up above normal.

The situation in the US has changed. The stimulus package will drive up the pace of growth and accelerate convergence towards the pre-pandemic activity trend. Meanwhile, Brent prices will remain lofty as a result of fundamental changes on the oil market shaped by the White House’s decision on oil and gas drilling. This marks a structural shift on the market, as US oil drilling will not be as straightforward as it was during the previous administration. The fall-off in oil output since March last year may not be reversed quite as readily as expected, thereby leading to a long-term change in the market’s balance.

The combination of these two factors – growth and oil prices – is set to translate into higher rates in the US, even if the Fed continues to act both now and over the years ahead. The low point for US rates is now in the past as a result of stimulus moves.

How can the euro area benefit?

We observe an imbalance between the United States and Europe, with the rise in interest rates originating in the US, while Europe is merely subject to it.

This disparity – broadly shaped by the President’s actions – clearly harks back to the time of Ronald Reagan’s stimulus moves. The US launched their stimulus programs at a time of alarm in Europe as the old continent failed to get back on the growth track after the second oil shock. French stimulus programs in 1981 had failed, monetary adjustments after the European Monetary System (EMS) was set up led to some instability and Europe was in doubt about its future. Meanwhile the political landscape was the most challenging, marked by eurosclerosis – with European integration stagnating – and the Pershing missile crisis, which set Europe between the US and the USSR.

After Reagan’s election in 1980, his massive recovery drive kicked off in 1981 – a very Keynesian program to drive domestic demand, which very soon pushed up US interest rates.

This asymmetry between the US and Europe led to an unprecedented widening in the yield spread between the two continents. The interest rate market was not really integrated internationally at that stage, so a partitioned market meant differentials developed on a lasting basis. One of the Reagan administration’s achievements was actually expediting this financial integration and offering a much larger scale for the funding of the US economy. This was the time when finance really took off and central banks cemented their predominant role in steering macroeconomics.

These partitioned markets meant that spreads remained very wide, with each interest rate figure translating the local situation for its country’s economy. One of the major upshots of this situation was an unrivalled appreciation in the dollar, which hit a high in February 1985. Interest rates had risen very quickly at the time, while inflation was beginning to ease. The real rate on the US 10-year – measured by the nominal rate less inflation – surged much more dramatically than the European real rate, thus supporting a rise in the value of the greenback.

If we are to ward off a speedy surge in European yields and avoid snuffing out the recovery too soon, the ECB must stay active and keep on buying public securities as planned. If we look at the ECB’s purchase pledges and governments’ planned issues, the ECB’s purchases should be higher than net public debt issues right from March. This would be a good way to keep rates very low in the euro area, at a time when the Fed cannot have the same grip on the market due to the hefty public deficit across the pond.

Intervention from the ECB could replicate market partitioning of the early 1980s and promote a rise on the dollar, facilitating a broad-based recovery in Europe.

The US rescue package could then offset the lack of an equally ambitious growth recovery plan in Europe and the euro area. The plan put forward by the Commission is more structural and should support the transition in economic activity in Europe over the years ahead. However, in the short term, the impetus to promptly get back to the pre-crisis trend is sorely lacking.

So it is the ECB’s role to set the stage to ensure that yields stay low, while governments are responsible for promoting the permeation of the US stimulus program through to European economic activity. This will clearly have a smaller impact than in the early 1980s, as the US is now more dependent on China than it was then, but it is crucial to pull out all the stops to draw the benefits from this situation and avoid being the world economic laggard as was the case ten years ago.