Climate Rupture

The summer of 2023 is a period of climate disruption. The month of June is the hottest ever recorded, ocean temperatures are dramatically rising compared to the past, including 2022... This accumulation can define a New Normal as suggested by the World Meteorological Organization.

However, this new framework does not appear stable as climate events continue to occur and their consequences accumulate.

Discussions on this new framework.

The World Meteorological Organization mentions the concept of a New Normal, a new framework for the climate. This theme is the subject of an editorial in the Financial Times. It is also discussed in an article in The Times of London.

This question deserves attention because the two approaches from British newspapers do not overlap.

According to the FT, the New Normal reflects the particularly concerning situation experienced this summer regarding climate. The New Normal means having 20 days of intense heat (40°C) continuously in Phoenix, Arizona; breaking records for ocean temperatures; and experiencing intense heat in Beijing and southern Italy. The magnitude of wildfires in Canada and heavy rains in the US or Spain also fit into this definition.

All these concurrent events, each significant on its own, are integral parts of the emerging new framework. It is no longer defined historically with local specificities and without global upheaval.

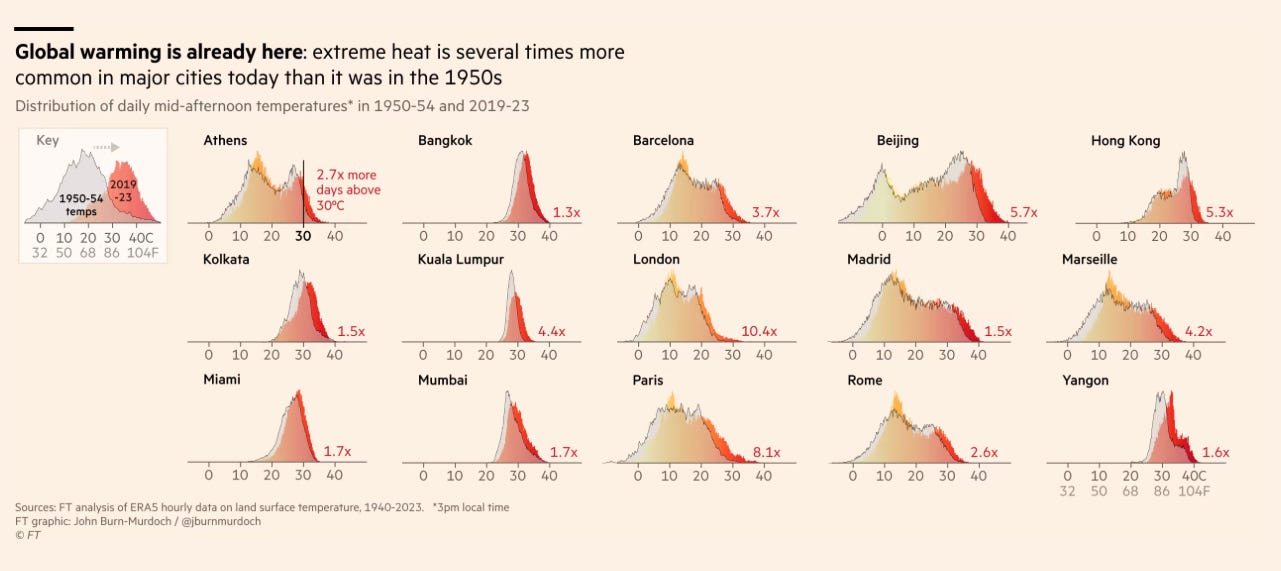

The world is tipping without the possibility of going back. Even if the temperature converges to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, these climate events will not disappear. This tipping point is noticeable when reading the graph taken from a recent article in the Financial Times that compares temperature distribution between 1950-1954 and 2019-2023. This distribution has shifted to the right everywhere. On average, it is much hotter recently than in the 1950s.

In Paris, the number of days with temperatures above 30°C has multiplied by 8 over this period and almost 6 times more in Beijing. It is this shift that raises alarm.

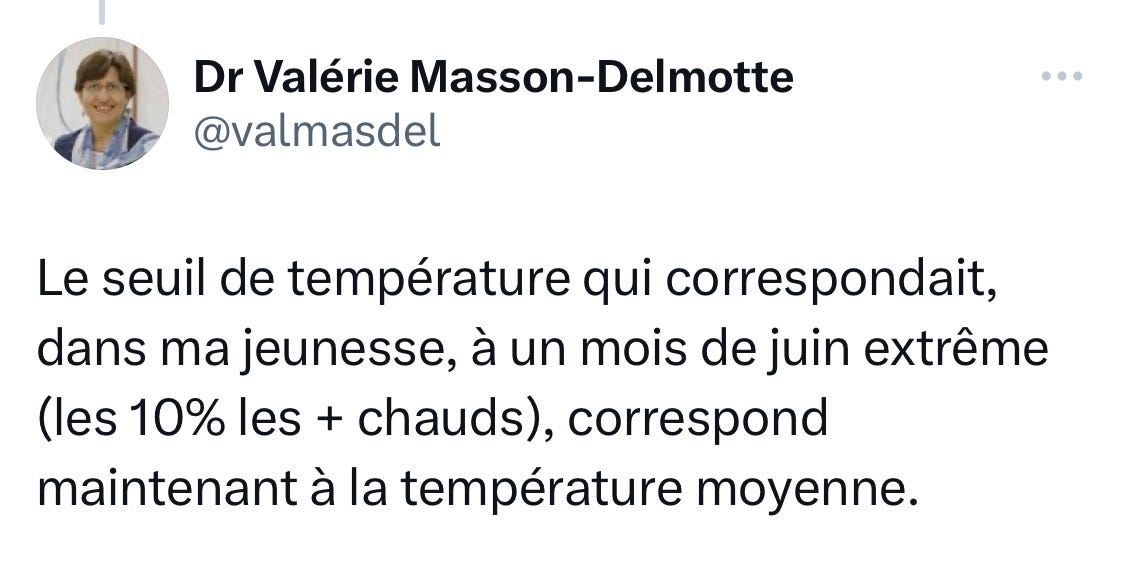

In her own way, this is what Valérie Masson-Delmotte expressed in a Twitter thread: "The temperature threshold that used to correspond, in my youth, to an extreme June month (the hottest 10%) now corresponds to the average temperature".

The world has changed due to the intensification of climate events. The perception that everyone can have of it has also deeply changed. Citizens are now becoming aware of climate change and its effects.

This new framework, made up of intense climate shocks and awareness, is here to stay. We will all have to adapt or even resign ourselves to it.

However, this approach to the New Normal is not satisfactory. It reflects the perception that today's world will not be like yesterday's but is consistent with tomorrow's. It is somewhat a representation of a system that oscillates around a horizontal trend. The New Normal would then result in an elevation of the horizontal trend and an increase in volatility around it. This new regime would define this New Normal. However, there is a perception that the distribution is not symmetrical and that there is a bias towards upward movement. Therefore, the new trend cannot be stationary.

We cannot assume that the world revolves around a stable trend. It does not appear to be able to be horizontal or even linearly upward (a line with an upward slope). Recent developments suggest that the trend is not independent of fluctuations but rather these fluctuations cause sustainable accelerations that pull the trend upwards.

Therefore, if fluctuations increase in amplitude and duration, it is illusory to think in terms of the New Normal unless one considers it as merely a rupture, which is a somewhat limited understanding.

Four dimensions prevent us from entering into this logic that relies on the idea that the worst is over, which is somewhat the idea of a New Normal in the form of a rupture.

1- Governments make divergent choices regarding 1.5°C.

After COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, states' commitments to the Paris Agreement indicate a temperature increase of at least 1°C compared to the defined objective at that time. This has considerable consequences for the global economy and world society. This is shown in the table below.

Drought periods will be much longer than those currently observed or those that would be observed with 1.5°C. Agricultural production will be further reduced and climate migrations will be much more significant. In this case, the global economy and society would not have clear common factors with the current economy even after the rupture we are currently experiencing

2- Energy transition involves a drastic reduction in the use of fossil fuels over the next thirty-five years by 2050.

In 2022, the consumption of these energy sources accounted for 80% of primary energy consumption. To align with the carbon neutrality trajectory, it would be necessary to reduce at least half of this consumption by 2050. Can we imagine that this transition will happen smoothly and that the energy transition will occur without noise?

3- This is also Adair Turner's argument in a recent article in the FT. He believes that there will be no problems with raw material supplies for manufacturing renewable energy sources, but mainly a problem with arranging investments over time. Going too slowly could disrupt the balance, creating more volatility and uncertainties about climate.

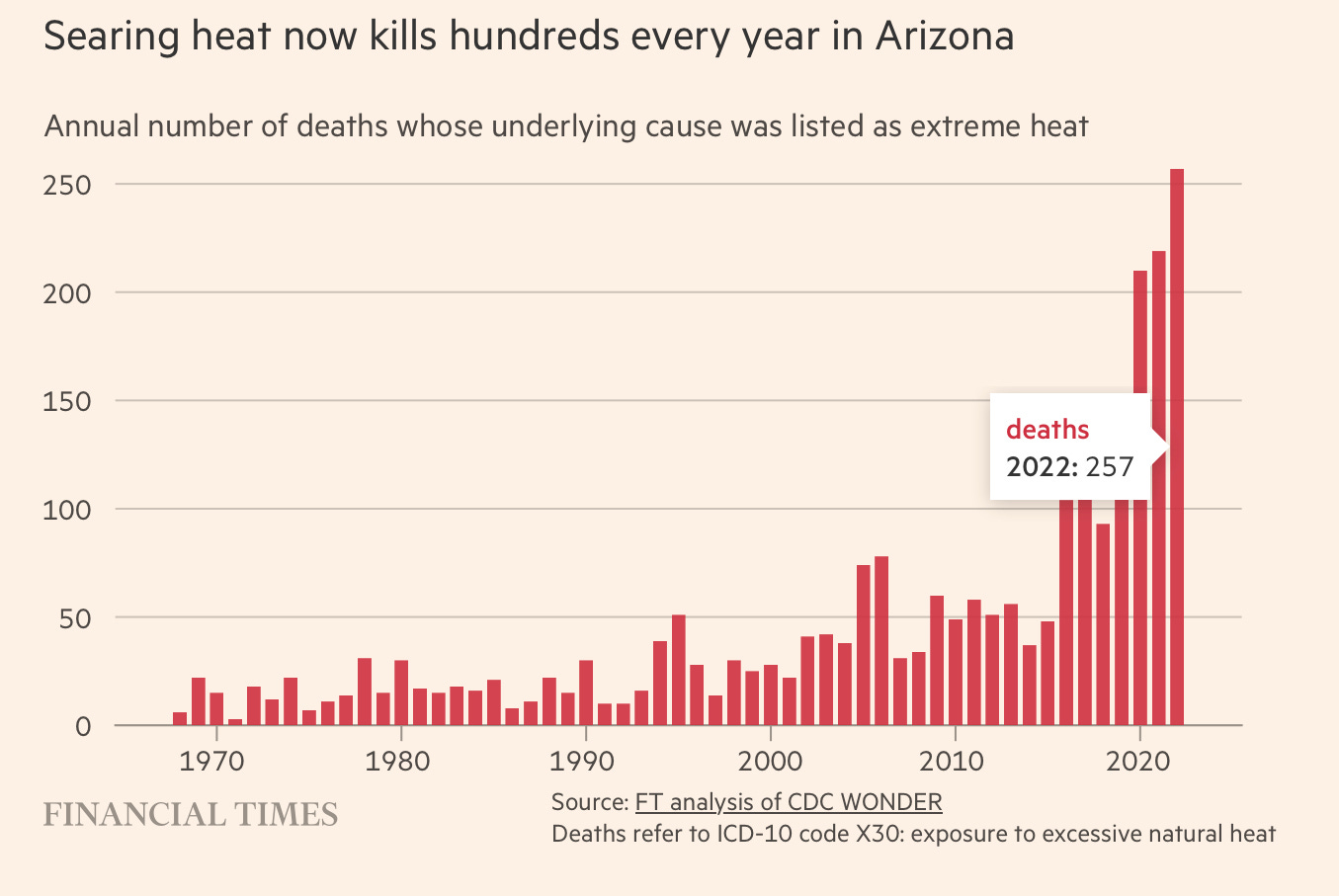

4- The disruptions have already begun. The shocks are already significant. In Phoenix, Arizona, the number of climate-related deaths has already shown a rupture. The continued increase in climate events could accentuate this phenomenon. The heatwave experienced by Phoenix recently will not be without consequences on the number of deaths in 2023

If there is a rupture and an inability to go back, it does not mean that the world is at a standstill. The increase in climate events in 2023 suggests that the situation could continue to deteriorate for some time. The climate regime will not spontaneously stabilize. Therefore, we cannot assume a relatively stable framework after a rupture.

What is emerging is the obligation to constantly adapt and make the necessary investment efforts for the situation to effectively stabilize. From this point of view, the increase in investments in renewable energies is good news (the IAE believes that the additional demand for electricity will mainly be met by renewable energies). This movement needs to be further intensified. The problem is that we are acting a little too late. What we are observing is not a surprise, unfortunately, for those who have been following the work of the IPCC for many years.

It's unfortunate that we need effective and dramatic evidence to take action.

_______________________________________

Philippe Waechter is Chief economist at Ostrum AM in Paris