Central Bankers are too shy when inflation jumps

Central bankers are meeting this week. The Fed will give its verdict on Wednesday while the ECB and Bank of England speak on Thursday.

This series of meetings comes as inflation rates escalate month after month. The figure is close to 7% in the United States in November and close to 5% in the euro zone. These very high measures of the evolution of consumer prices have not yet really piqued the interest of central bankers while numbers are well beyond the targets they set.

No central bank has threatened to abruptly change the frankly accommodative nature of its monetary policy whereas price stability is at the heart of their mandate. Central bank independence in the 1980s found its rationality in the ability of an independent central bank to fight inflation quickly so that the higher inflation momentum did not penalize growth.

The Bank of England had been deluded last month, but comments by members of the Monetary Policy Committee did not result in a change in interest rates.

It must be said that central bankers are trapped in a strict framework that they themselves have put in place. To get out of accommodative monetary policy, the scheme is to first halt asset purchases before any rise in interest rates. This gives inertia to the decision-making process and an inability to intervene as soon as necessary.

The other questionable aspect of monetary policy is taking into account too systematically the expectations and reactions of economic players. This is reflected in the desire of central bankers to indicate what they are going to do in the future (forward guidance) in order to orient expectations so that the announcement of a measure does not create a rupture. Janet Yellen had done this remarkably after December 2015. This method, however, drastically reduces the ability of central bankers to intervene quickly.

Expectations of a rise in interest rates in the second half of 2022 are at the heart of this forward guidance, but does this make sense if the duration of inflation is limited in time. It cannot be ruled out that by this time, the second part of 2022, the inflation rate may have returned to a zone close to 2%. What would then have been the role of monetary policy?

Fiscal policy, at the heart of the demand shock that created this inflationary pressure, will have had a more important role in the management of changes in consumer prices.

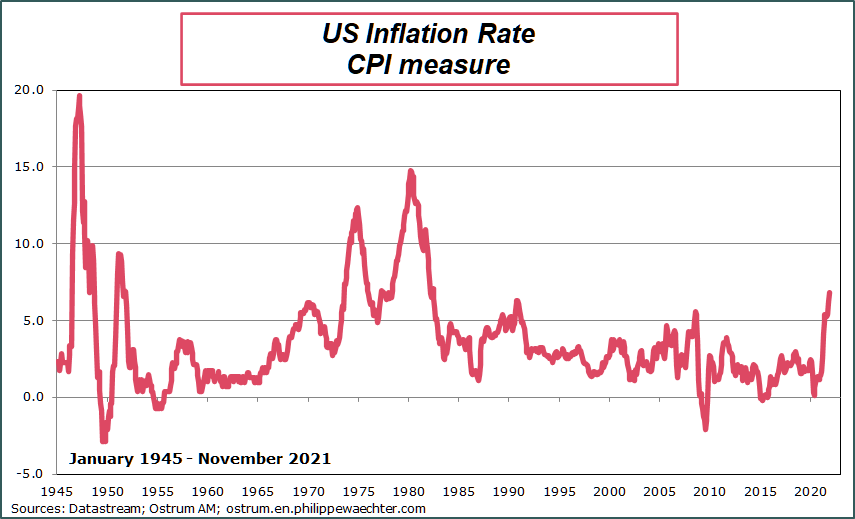

Moreover, central banks are not showing an unshakeable will to change the path of inflation, thus reflecting an inability to choose. Is the inflation profile that of the years 46-48 in the USA when the return to normalcy of the economy after the war and the deprivations resulted in a high inflation rate close to 20% . Or is the current period looks like the 1970s with higher inflation over time.

he accelerating demand for goods and the impact of the shock on supply suggest that the current period is closer to the years 46/48 rather than the 1970s when a real supply shock resulting from the sharp rise in the price of oil and the instead of the indexation clause of wages on prices had caused the persistence of inflation.

Without clearly defining themselves, central banks seem to be making this choice of inflation that is limited in time and without any real mechanism of persistence. Because for inflation to be sustainable, a specific mechanism that creates persistence is needed, like the indexation of the 1970s.

Unable to express a choice, central bankers are unwilling to rush the adjustments so as not to derail the recovery in activity. A central bank that hikes its rates quickly and suddenly would take the risk of penalizing its own economy. Indeed, the shock on supply resulting from the violent increase in demand for goods takes place in a globalized economy where production processes are internationalized. Since all developed countries experience high inflation and a shock on supply, restrictive monetary policy would penalize local businesses to the benefit of foreign competitors. Central banks cannot play this game.

They can only intervene in a coordinated manner in order to have a global consistent framework that will not hurt and unbalanced the growth momentum. The expectation one would have at central bankers’ meetings this week is a series of consistent measures from central bank to central bank to avoid any imbalance. Such coordination has already existed in the past in times of crisis in order to provide the necessary liquidity. This has generally been effective. Today, however, the challenge is no longer on the liquidity of financial markets but on the ability of economies to ward off an inflation rate that is too high. It is more complex because each economy reacts differently depending on its own economic structures, especially on the labor market.

The other difficulty with a cooperative scheme is that you have to take into account China, whose current constraint is not inflation but growth, which is slowing rapidly. The stakes, moreover, are not the same for the United States or for the Euro zone vis-à-vis the Middle Empire. Will the Americans favor their alliance with Europe or the interest shared with the Chinese? This dilemma rejects any ability to coordinate monetary policy in Europeans and Americans.

* * *

In this inflationary episode in developed countries, it appears that central banks are procrastinating in the message they must send to the players in the economy. Unable to intervene suddenly and therefore out of step with their mandate on price stability, they are slow to clearly define their strategy. Powell thus moved on from a speech on a transitory rate of inflation which would no longer be. This reassured investors but does not reassure the ability of central bankers to analyze and deal with this acceleration in inflation. If they think inflation is close to that of the years 1946/1948, it must be said clearly. If this is not the case, we are entitled to expect specific action from the monetary authorities.

In fact, the real risk is that central banks have lost control.